Bessie Coleman was born in Atlanta, Texas in 1892, the child of illiterate sharecroppers. Though her childhood was spent working the cotton fields with her parents, she constantly yearned for more. Years later she would become the first civilian licensed African-American pilot in the world, and practically invented the idea that women could fly — making her one of the top aviation industry inventors in the world.

For several years, she toured the country dazzling crowds with her barnstorming and parachute jumping. Fulfilling her dreams of flight sparked a revolution and paved the way for future generations to pursue their own ambitions — but her story, inspirational at first, ended in unspeakable tragedy.

Early life and education

Bessie Coleman was born on January 26, 1892, in Atlanta, Texas, the eleventh of thirteen children. Her parents, Susan and George Coleman, were sharecroppers, and the illiterate children of slaves.

The large family worked the fields together, tending cotton, and did what they could to make ends meet. When Bessie was just two years old, her father moved the family to Waxahachie, Texas, where he bought a quarter-acre of land and built a three-room house in which the final two children were born.

Just seven short years later, George left the family to return to his home state of Oklahoma. Bessie’s mother, left alone to raise 13 children, was forced to find work, along with Bessie’s two older brothers. Bessie, in turn, became caretaker for her two younger sisters.

Somehow, the young girl still managed to walk miles to her one-room segregated schoolhouse every day. An apt pupil, she would spend her evenings reading to her mother and siblings — but she constantly yearned for more. After completing all eight grades (as rumor has it, all in one year), she found work as a laundress and saved her pennies. Finally, in 1910, she took her earnings and enrolled in the Colored Agricultural and Normal University in Langston, Oklahoma. Bessie completed only one term before running out of money and returning to Waxahachie.

An unlikely dream

Once again, Bessie found work as a laundress until in 1915, at the age of 23, she had saved enough to move to Chicago and stay with her brother Walter. All she was looking for was a better life.

During that time, hundreds of thousands of people from the black community in the South moved to Chicago and other Northern cities, in what’s been dubbed “the great migration.” They created community organizations, businesses, music, and literature. Still, life wasn’t easy for a young African American in the early twentieth century, no matter where they lived, and it could be just as difficult to find work and housing in Chicago as it had been elsewhere.

Bessie, for her part, became a beautician and worked as a manicurist in the barbershops of Chicago’s south side, where some of her clients were veterans of World War I, the first war to use airplanes. She loved their stories of adventure and dreamed of flying on her own one day.

Goaded on by her brother John who teased, “I know something that French women do that you’ll never do — Fly!” she decided that somehow, she would make that dream a reality.

Learning to fly

As luck would have it, Bessie met Robert Abbott, publisher of the nation’s largest African American weekly, the Chicago Defender, in those same barber shops. Abbott encouraged her ambitions and when Bessie couldn’t find a pilot willing to teach her to fly in the states, he suggested that she attend school in France. According to him, the French weren’t racists and were the world’s leaders in aviation.

Abbott was so serious about his suggestion that he offered to sponsor Coleman in her quest for a pilot’s license and, along with banker Jesse Binga, funded her entire trip. For Abbott’s part, he was hoping that Bessie’s success would bring his paper, and African Americans, good publicity.

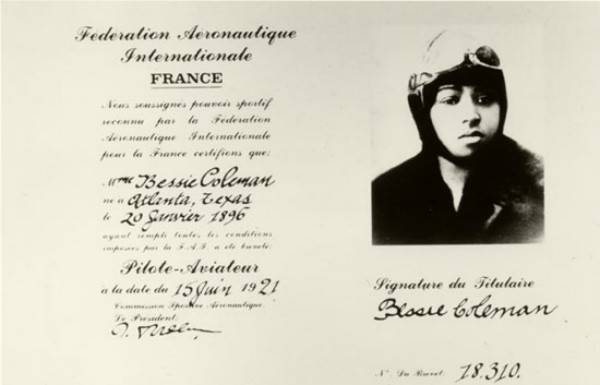

Bessie departed for France in November 1919, where she studied under a WWI ace who had downed 31 German planes. The first school she applied to didn’t take female applicants because two had died in training there, but she completed training at the well-known Caudron Brother’s School of Aviation and was awarded her Fédération Aéronautique Internationale (F.A.I.; international pilot’s license) license on June 15, 1921.

Unexpected celebrity

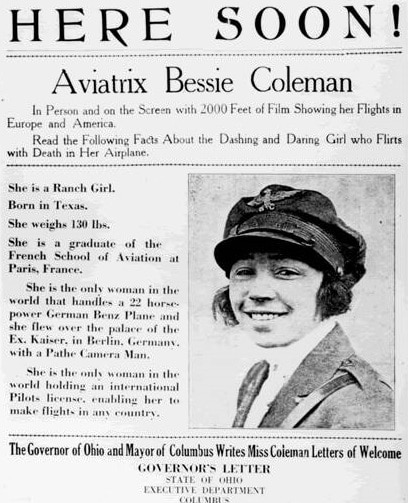

Returning to New York in September 1921, Bessie was greeted by an avalanche of press coverage arranged by her banker friend. Speaking to reporters, Coleman said she planned to found a school for aviators of any race and that she would speak to audiences in churches, schools, and theaters to spark the interest of other African Americans in the technology of flight. African American newspapers around the country quickly dubbed her “Queen Bess.”

Coleman quickly realized that the best way for a pilot to make money was flying for entertainment (or being a stunt pilot), but she didn’t possess the necessary skills. Again, she headed to France for more training.

When she returned to the United States for the second time, Bessie already had the publicity she needed to attract paying audiences. Her first appearance was an airshow on September 3, 1922, at an event honoring veterans of the all-black 369th Infantry Regiment of World War I. The show billed Coleman as the “world’s greatest woman flier” and featured aerial displays by eight other American ace pilots.

A plane of her own

In 1923, Coleman purchased a small plane of her own but promptly crashed. The plane was destroyed and Bessie was hospitalized for three months due to the resulting injuries. It took almost two years to earn enough money to put a down payment on a second plane, an old Jenny JN-4 with an OX-5 engine.

Bessie then traveled south, where she gave a series of lectures in black theaters in Florida and Georgia. She opened a beauty shop in Orlando to earn the money needed to start her aviation school and, using borrowed planes, continued exhibition flying.

A tragic ending

In 1926, Bessie made the final down payment on her plan and arranged to have it flown to Jacksonville, FL, where she was scheduled to give a benefit exhibition for the Jacksonville Negro Welfare League.

William D. Wills, who by varying accounts was either her mechanic or a hired pilot, was forced to make three landings on the way because the plane was so worn and poorly maintained.

On the evening of April 30, 1926, she and Wills took the plane up for a test flight. Wills was the pilot and Coleman, in the second cockpit, had her seatbelt unattached so she could lean out over the edge of the plane to pick out the best location for her program the following day. When the plane malfunctioned at 1,000 feet, it dived, then flipped, throwing Coleman to her death.

When her body was found, there was a letter in her pocket from a 12-year-old African American girl telling her she wanted to be an aviator one day.

But there's more. Check out these bussin stories:

- Fat Food / Drink For the guys SMH

Body positivity is for women, not lazy white guys with dad bods There is more to dad bod positivity than meets the eye. It's appropriation of body positivity culture created by and for women—by the usual suspects.

Body positivity is for women, not lazy white guys with dad bods There is more to dad bod positivity than meets the eye. It's appropriation of body positivity culture created by and for women—by the usual suspects. - Food / Drink SMH

7 annoying statements you hear from every white waiter Eating out is a luxury sullied by the insipid banter diners are subjected to by their servers—and it needs to S.T.O.P.

7 annoying statements you hear from every white waiter Eating out is a luxury sullied by the insipid banter diners are subjected to by their servers—and it needs to S.T.O.P. - SMH

Inside the ‘black pill,’ the web’s worst ideology Black-pillers see the world as a hopeless, meaningless struggle, and themselves as trapped in a terrible, unescapable condition.

Inside the ‘black pill,’ the web’s worst ideology Black-pillers see the world as a hopeless, meaningless struggle, and themselves as trapped in a terrible, unescapable condition.

What an incredible life. ………And you’ll never see Hollywood acknowledge her, they need to make the 76th movie about Amelia Earhart.