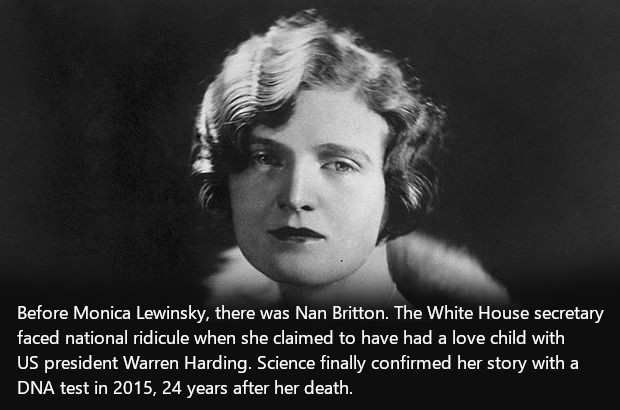

For a 1929 scandal, this one still remains juicy. Headlines read, “DNA test reveals Warren Harding’s hanky panky.” Another claims “Warren Harding: America’s Horniest President.” They call Nan Britton’s baby a “love child,” and Britton herself a tell-all mistress.

Were Britton alive today, the modern day revelations about her private life might be featured on the front page of a celebrity tabloid, or on daytime TV with Maury pointing to President Warren Harding and pronouncing, “You are the father!”

Instead, Britton and Harding’s families have to settle for this genealogical truth: tests confirm what Britton long claimed — her daughter, Elizabeth Ann Blaesing, is indeed Harding’s biological child.

Before he was President, Harding was just a family friend to young Nan Britton, who became infatuated with the charming, handsome newspaperman. Concerned with his daughter’s crush, Britton’s father asked his friend to speak to her, to allay her schoolgirl crush. Instead, their secret love affair began. It continued throughout his presidency, right up until his death, when the child support payments ended and the truth about the pair was revealed.

Britton is just another one of history’s forgotten women, cast aside and lost between the pages of textbooks.

She’s not alone; there’s Vera Nabokov, the writer’s devoted spouse and saver of Lolita; there’s Hadley Richardson, Ernest Hemingway’s first wife; and Beryl Markham, aviator and American expat who lived wildly and wondrously in Africa. Only no are these women beginning to come to light, to take their rightful place in history.

The latter two have been resurrected in Paula McClain’s fiction: in the 2011 novel The Paris Wife, and in 2015’s Circling the Sun, but McClain isn’t the only one exploring these forgotten women’s lives. Megan Mayhew Bergman’s short story collection Almost Famous Women, published earlier this year, explores the lives of thirteen overlooked women, including Beryl Markham.

NPR’s Maureen Corrigan said of the collection that “generally speaking, most of the ‘almost famous’ women in this compelling collection fit in that intriguing category — trouble either found them or they stirred trouble up.”

Of her subjects, Bergman said, “I think many of these women were keenly aware that if they chased dreams instead of building families or setting up camp under the safety of a husband, they would face challenges later. There is a line in the books that underscores this idea: the world has not always been kind to its unusual women.”

Herstory is a 1960s term I learned through feminist zines, a response to the male-dominated history taught in schools and regarded as fact. But today’s rebirth of these bold, badass women is less a clever catchphrase and more a powerful movement. As New York Times writer Peter Baker said in an article on Britton, through technology and thorough research, these women are “rewriting the nation’s history books.”

It took nearly a century for Nan Britton’s truth to be exposed, but not for lack of her own effort. She wrote and self-published The President’s Daughter, a tell-all to raise money to raise her daughter, but it was shunned by publishers and regarded as lies by Harding supporters.

In a TIME article, Robert Plunket deems her writing “Nabokovian,” but that’s not meant to be a compliment — he goes on to call her a “calculating, acquisitive woman.” Of her memoir, he says, “sometimes you want to warn her. Other times you want to shake her. (Never, though, do you want to hug her.)”

Calculating, acquisitive woman. And why shouldn’t she be? She had a daughter to feed and clothe and shelter. She was in her early twenties, in the 1920s. Her child’s father, who had provided for her in the last years of his life, had suddenly died. What else was she supposed to do?

She self-published the book, bravely, in the face of threats from the Harding family, from Congress members, from the press, and though it sold like crazy, it wasn’t enough. Her story was dismissed as vindictive fiction, until science, with that DNA test, made us accept what had long been whispered.

Dismissing these women is nothing new, though. Take Markham: her memoir West With the Night has long been plagued by rumors it was really written by her third husband, and it did not become popular until 1982, when George Gutekunst discovered not the book itself, but rather Hemingway’s praise of it.

Optimism tells me it would be different were these women to live and publish today, but my pessimism nags at me, convincing me it wouldn’t be true. Look at Monica Lewinsky; look at every athlete’s discredited or publicly shamed “other woman.”

Even now, history is not kind to unusual women. Plunket, despite his self-proclaimed obsession with Britton, writes of Harding that “when the drama of her pregnancy strains the relationship, you really do feel for him.”

Her pregnancy. As if it was all her doing, a solo act. Wasn’t it also Harding’s decision to have sex with a young girl? Even now, stories reporting the results of the DNA testing mention Harding’s fallen grace, his tainted image. It was Nan, though — and Elizabeth — who lived with the public shame.

Like all celebrity scandals, this too will fall away, lost beneath the clutter, and another unusual woman will be lost to history until someone decides to fictionalize her life. For now, though, let’s remember it as herstory — Nan Britton, who was a human woman, with all the complexities that entails, and who deserved so much more than history has given her.

But there's more. Check out these bussin stories:

- Beauty

8 weird body mask beauty products you have to try Your face is obviously getting a lot of TLC, but your body could be missing out.

8 weird body mask beauty products you have to try Your face is obviously getting a lot of TLC, but your body could be missing out. - Love SMH

Woman turns all the creepy pickup lines she gets into hilarious illustrations Artist Emmie Tsumura found a creative way to channel all of the creepy messages into a creative art project.

Woman turns all the creepy pickup lines she gets into hilarious illustrations Artist Emmie Tsumura found a creative way to channel all of the creepy messages into a creative art project. - It Happened To Me Love

My violent vibrator somehow shook the infertility out of me We hadn't bought it for the purpose of conceiving, but that's exactly what happened (finally!) after the very first time I tried it.

My violent vibrator somehow shook the infertility out of me We hadn't bought it for the purpose of conceiving, but that's exactly what happened (finally!) after the very first time I tried it.

Love this. GJ.